This final chapter of the book sums everything up and has lots of highlightable sections. Mainly though it wraps up its academic argument against the “current” way economists use rational choice models to explain to policymakers how to deal with CPR problems. Ostrom is pushing for a new “framework for analyzing problems of institutional choice.” In a slight to economists, she notes:

CPR situations are rarely as powerful in driving participants … toward efficiency as are competitive markets. … following short term profit maximization in response to the market price for a resource unit may, in a CPR environment, be exactly the strategy that will destroy the CPR, leaving everyone worse off. Nonmonetized relationships may be of importance.

She criticizes idealized models which control for a single variable as too narrow for policymaking, and argues that a more flexible framework that takes into account situational variables is the better path. The book shows how the situational variables variable are best read by those that are closest to the CPR. This does not mean government can’t be involved: “Forms of public instrumentalities were also used … but none of the success cases involved direct regulation by a centralized authority.” Stable political systems, and the California judicial infrastructure are examples.

In the final pages she sums up:

The intellectual trap in relying entirely on models to provide the foundation for policy analysis is that scholars then presume that they are omniscient observers able to comprehend the essentials of how complex, dynamic systems work by creating stylized descriptions of some aspects of those systems.

Her conclusion:

First, the individuals using CPRs are viewed as if they are capable of short-term maximization, but not of long-term reflection about joint strategies to improve joint outcomes. Second, these individuals are viewed as if they are in a trap and cannot get out without some external authority imposing a solution. Third, the institutions that individuals may have established are ignored or rejected as inefficient, without examining how these institutions may help them acquire information, reduce monitoring and enforcement costs, and equitably allocate appropriation rights and provision duties. Fourth, the solutions presented for “the” government to impose are themselves based on models of idealized markets or idealized states.

I think this quote she has is

:

:

Most modern economic theory describes a world presided over by a government (not, significantly, by governments), and sees this world through the government’s eyes. The government is supposed to have the responsibility, the will and the power to restructure society in whatever way maximizes social welfare; like the US Cavalry in a good Western, the government stands ready to rush to the rescue whenever the market “fails”, and the economist’s job is to advise it on when and how to do so. Private individuals, in contrast, are credited with little or no ability to solve collective problems among themselves. This makes for a distorted view of some important economic and political issues. (Sugden 1986, p. 3)

Her dream expressed:

If this study does nothing more than shatter the convictions of many policy analysts that the only way to solve CPR problems is for external authorities to impose full private property rights or centralized regulation, it will have accomplished one major purpose.

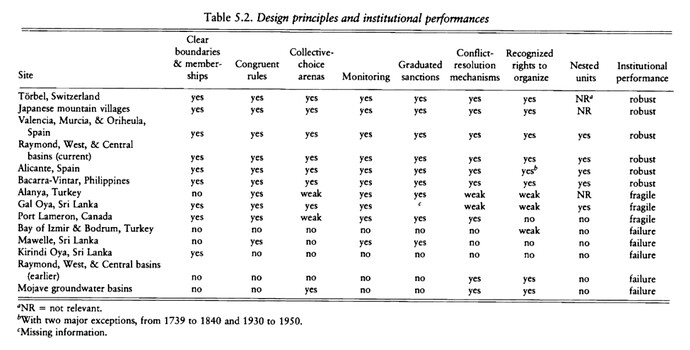

Most of the chapter she runs through the various elements of her 8 Principles including things like developing rules for use, information transparency, monitoring, graduated sanctions, and also how to change/develop a system.

She also points out that this is for smaller communities of CPRs, which is a key point. Size matters under her framework. This is also why she talks about “nesting” to achieve scale:

But once the smaller units are organized, the marginal cost of building on that organizational base is substantially less than the cost of starting with no prior base.

eg.

Eventually the system that evolved in Gal Oya was four layers deep.

and the statement:

A theory of self-organization and self-governance of smaller units within larger political systems must overtly take the activities of surrounding political systems into account

After recently reading Seeing like a State and Two Cheers for Anarchism I was very happy to see this kind of bottom-up, federated approach.

One section I found interesting is where she discussed how when you are developing your CPR community, you can learn the “wrong lessons”. In California:

Instead of applying the lesson by starting with small incremental changes at the basin level before attempting to build interbasin institutions, they went to the interbasin level first, before designing intrabasin institutions. What worked as an incremental bottom-up strategy at the basin level did not work when attempted at a regional level.

There are no shortcuts to building a healthy CPR community. You have to start with the people closest, slowly iterate, maintain good relationships and information flows, be in a relatively stable political environment, and just figure out the rules and the system for yourselves.

One last takeaway for me: “Crisis” politics. Noting that “[i]ndividuals weight, for example, potential losses more heavily than potential gains” she says:

The propensity of political leaders to discuss CPR problems in terms of “crises” is far more understandable once one takes into account that individuals weight perceived harms more heavily than perceived benefits of the same quantity.

Which makes me think a lot about how the climate crisis is positioned. Maybe we need to take her advice and talk more about the positive gains we could reap if society moved towards more green interactions. Solarpunk, anybody?